' This form of government [constitutional] does not invade the inner life of man.' Arima Tatsuo, The failure of freedom: a portrait of modern Japanese intellectuals.

I

Language is a living system. If its productions (culture, memories and behaviors)

are to endure, it cannot be in books or museum depositories alone, but entrusted

to the living body itself, molded along the folds of time. This essay examines

the experience by first graders in a Japanese public elementary school of learning

writing and reading, and puts it in regard with religious practices (rites and

exorcisms) that are inextricably linked to language practices —both as

a record of their historical and political background as well as the ongoing

demonstration of the potency of their effects, which perhaps includes the preservation

of the emperor institution. The essay also endeavors to question the meaning

of an aesthetic experience that participates in the general and quasi-instinctive

obedience to all forms of authority.

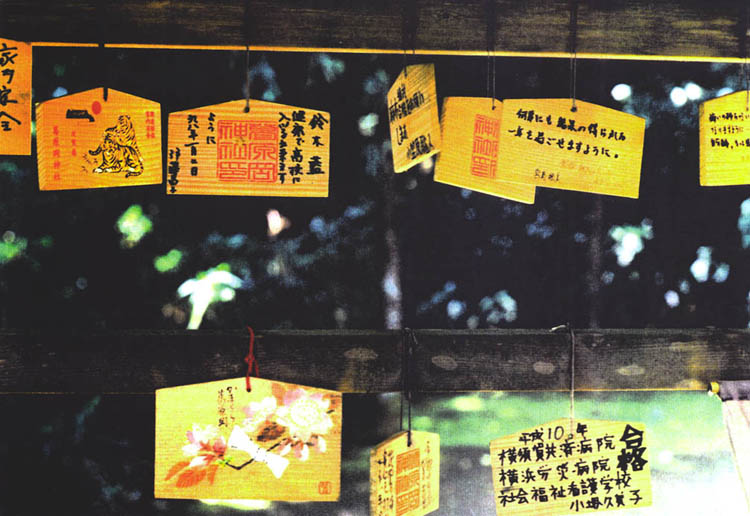

Pictorial votive offerings on wooden surface called ema where one writes one’s wishes.

The nature of the implications of a linguistic system on societal structures

is a vast question that remains largely unresolved. What the essay intends to

show with as much definition as possible is how a particular culture

of education passes to the young the mental make-up of the ancestors. Many Japanese

are struggling today with the question of the seemingly profound incapacity

of their country to move towards the implementation of needed political and

economic reforms. It is hoped that this work will foster an understanding of

how one generation against its own will repeats the gestures of the past. Writing

for historical reasons has been inordinately privileged in Japan, with the result

that ‘the successful adaptation of old symbols to changes of social

structures’ which A.N.Whitehead viewed as ‘the final mark

of wisdom in sociological statesmanship’ has been wanting

.

Family members bring wooden grave

tablets called toba to the grave of their ancestors. On

one side is written a prayer (sutra), and on the other one the name of

the person who makes the offering.

II

So it is not surprising that a ‘revolution in symbolism may be required’

(Whitehead again), and indeed twice in its history, in the 1880’s and in

1946, Japan considered whether changing its writing system (or systems, since

it is complex enough to require another one or two scripts to explain it) for

the Roman alphabet might be a necessary step towards democratic institutions.

Supporters and opponents of this radical reform became identified with clear

political positions. In 1945, preparing to surrender, the Japanese government

stated two priorities: save the emperor and preserve the Japanese language.

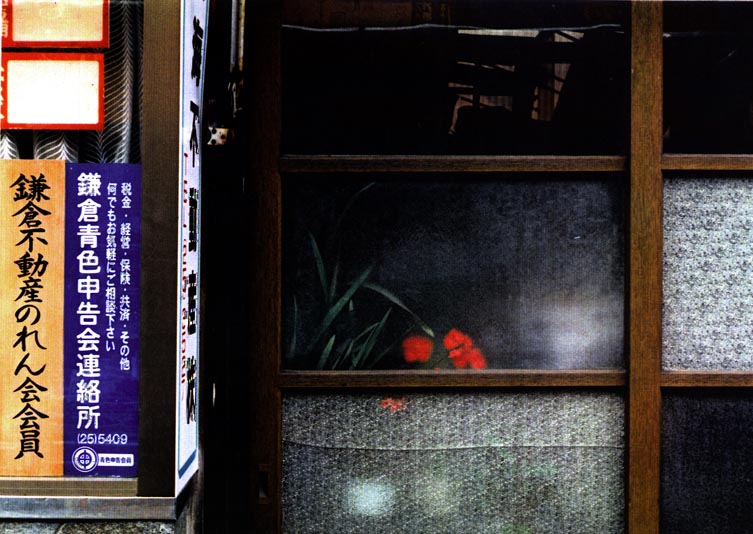

Kamakura. A haiku by Suishyu (18th century): Snow over Kamakura, I have to leave my dolls. The finger is on the Chinese character for ‘dolls’.

I lived in Japan between 1993 and 1999. On many occasions, I was able to observe

the role that language, especially writing, plays in the maintenance of social

behavior traits, and how it seems to succeed in conveying that two thousand-year-old

values matter, that they still matter today, and that they matter in every area

of life. I previously conducted in NY a study on the sound-shape of language

that resulted in the production of a video with linguist André Martinet.

I first heard of Japan (I was a high school student) in Eisenstein's remarks

on non-linear storytelling: instead of 1,2,3,4, the story delineated

in the Japanese scroll would run 1,3,2,4 —allowing for a knot (a twist)

along the way.

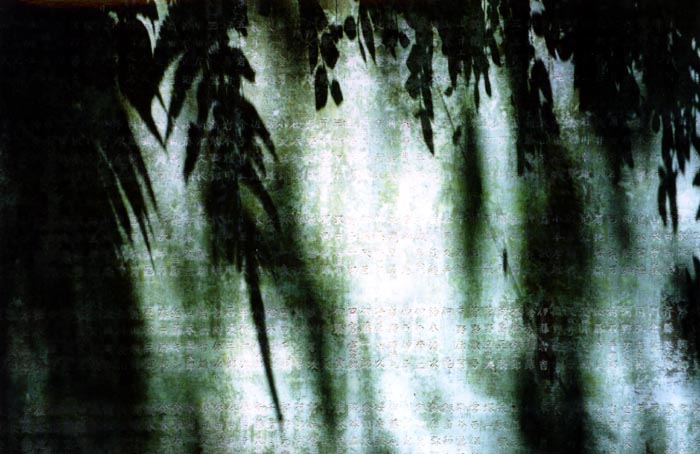

A fortune-paper called omikuji is tied to a string. Omikuji is a popular form of divination available at shrines. If the fortune is not favorable the strip of paper is often tied to a nearby tree or frame set up within the shrine ground to dispel the prediction and avoid bad luck.

One can observe today in Japan patterns of feudalism and a clan mentality. The Japanese are entangled in networks of obligations and duties that at times considerably restrict the exercise of personal judgment and the sense of responsability it entails; consequently, the group dynamics at every level of society allows changes only reluctantly and thus at a great cost, after lengthy deliberation, and often with the ‘help’ of outside, or foreign, pressure (gaiatsu).

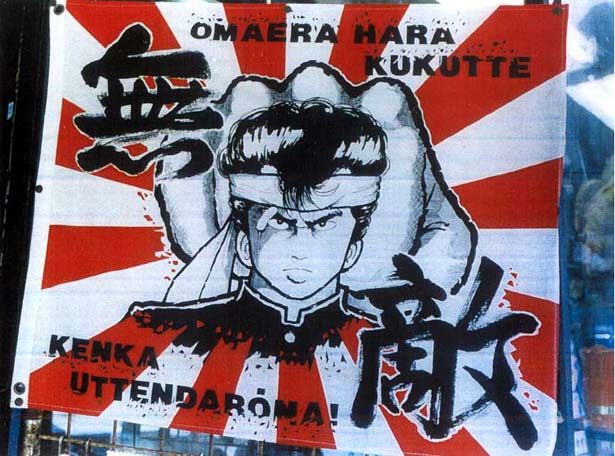

A recruiting poster from an extreme-right organization.

The romaji phrases read: ‘prepare yourself for the worst!’, and ‘pick

up a fight with somebody!’; the chinese characters mean ‘unbeaten’.

After looking at calligraphy, I realized that I needed to understand how this

art (or religion, really) of writing begins and grows in the individual. I decided

to see how young Japanese school children learn writing in their native language

—which the Japanese call koku.go (literally, the ‘national

language’) in contrast to nihon.go (the ‘Japanese language’)

used to refer to the language when spoken to and by foreigners.

With the help of a fellowship from the Canon Foundation in 1996, I was able

to observe for an entire school year the Japanese lessons of a class of first-graders.

I often videotaped the classes, and systematically kept documention of the exercise

sheets and other materials written and/or drawn during the classes. I also guided

the children through their first steps into my language. This experience presented

me with many fortunate encounters, gifts all, many of which haven't been opened

yet.

The exercice sheet of a student composing (writing/drawing) of a face with letters from the hiragana syllabary.

What was most striking for me in these Japanese lessons was the discipline of

the hand (indoctrination, one could say), and particularly how this self-control

develops with the grid that functions as a casing of the eye, keeping in mind

that eye here (at this age of life) means much more than the eye, for

reading and writing represent the most elaborate dialogue, mediated by the hand

and the voice, between the brain and the outside world.

April 15, 1997, elementary school in Yokosuka, first grade class. Two weeks into school (which in Japan begins April 1st.) the children are learning how to write their first letter, the hiragana for the sound [a], and which is made of three strokes.

In the photograph the teacher is writing the second stroke of the letter.

I came to understand that whereas Western societies are structured around the

law (normative essence) internalized by the members of the community, Japanese

society is structured around codes of manners and forms (kata), that

are pure exteriority (visibility); it is a society, then, that understands morality

(traditions and virtue) as corporeal ‘information’ (Kafka’s The

Penal Colony provides a literal rendition of a writing of the law onto the

surface of the body). It is a society where the person is exquisitely and tightly

wrapped, most famously in the kimono, and in many other enclosures, the most

pervasive one being language as it governs the developmental growth of the child

and directs behavioral transactions from individual to individual which, in

the end, given enough time and practice, constitute and validate a tradition.

Beauty and form can be intoxicating, when rigid compositions demand the harnessing

of the self onto a proper (rigid) sequencing of steps; there is then nowhere

else to go, and the mind remains frozen in its timeless productions, whose beauty

exudes a certain degree of sadness. Thus the last words (quoted by Kawabata

Yasunari in his Nobel prize speech) from the suicide note of Akutagawa Ryunosuke

(1892-1927) : ‘Nature is beautiful because it comes to my eyes in their

closing moments.’

An exorcism to oust evil spirits from the newly bought car is going to be performed by a Shinto priest.

The sign reads: ‘Ceremony of the great purification for cars’ (kuruma oharai jyo).

The other pivotal role writing plays in Japan is in the religious sphere. From

the very beginning writing came to Japan together with Buddhism —from China

by way of Korea (called at the time Paekche). The rites and ceremonies

incorporating writing are numerous, both in Shintoism and Buddhism, and writing

itself came to take on a sacred significance.

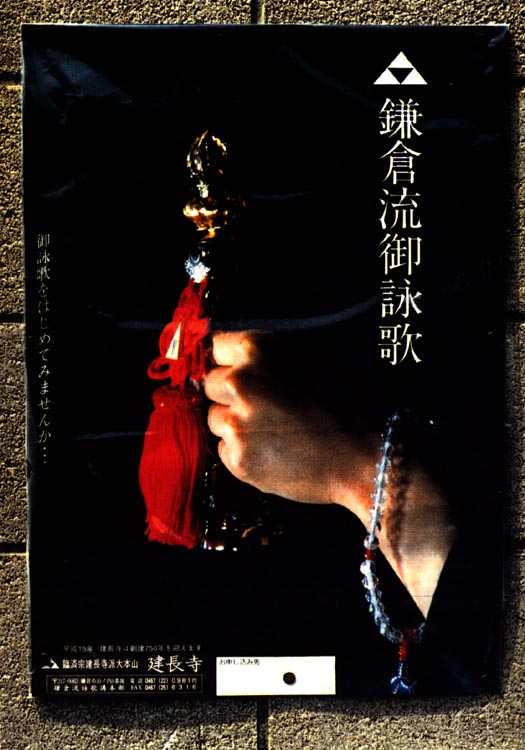

The vertical line on the right reads: ‘The Kamakura School of Pilgrim Songs’; the one on the left: ‘Why don’t you start learning pilgrim songs.’

It is a delicate matter for a foreigner to intervene in a other country's internal

affairs, and in Japan even more so. It is known that Japanese are not always

comfortable with foreigners who speak their language; they prefer the buffer

of a translation. Securing permission for access in an elementary school took

a full year. Japan has produced some of the fastest cuts in the history of cinema,

while concurrently evolving elaborate figures of slowness in art as well as

politics (literally, when, for instance, politicians would express their dissatisfaction

by walking to a parliamentary vote extremely slowly, a pace called ‘the

step of the cow’).

The research for this essay originated in the desire to understand how human

beings use their eyes and their hands, and, specifically regarding the Japanese

tradition, the cultural implications of graphic symbolization. I have two passions:

language and picture taking, still or motion. I see language as a mirror (interface)

between nature and nurture; studying it and teaching it allowed me to understand

better how nature develops and reclaims itself in cultural configurations. I

use pictures to study how forms, shapes, and structures establish relationships

between the body, the image, and time.

I believe that if the new multimedia technologies are to be beneficial to society,

it will be through the development of intellectual structures that associate

the word with the picture. The proposed essay will closely knit photographs

and texts together; it aims at bringing disparate motions of the mind into unity,

putting them to rest, so to speak. This is not without affinities with the treatment

of time in the practice of repetitive movements in martial arts drilling; or

in kabuki, in the frozen poses and stop-action movement, called mie,

when dancers pause at moments of muscular tension; or in period films (jidaï-geki),

when in the blink of an eye the motionless sword becomes a flash of lightning.

In cinema it is called (a) ‘cut!’; or, as David Hockney used to say,

‘The best [photographs] are those that bleed to the edges.’

Stele with a poem by KYOKA IZUMI (1872-1940)

" In a barren landscape

projecting its mass into the sky

a large rock witnesses the passing seasons..."

This project was supported by a fellowship from THE CANON FOUNDATION EUROPA.

I wish to express my gratitude to Hiroko TAMURA and all her pupils at the elementary school of Johoku shagakko in Yokosuka.

I am also deeply indebted to Margrit KELLER-NATORI, Mariko TAMAGAWA, Toru OTA, Madoka KAGA, Ikuhiko HIGE, Chikako KAWAHARA, Koun SUHARA, Yohji HAIJIMA, Teruo INOUE, Kohei OKAMOTO.